|

| Source: cis.org |

For the past two years, DACA has allowed undocumented young adults to avoid deportation and obtain a work permit and temporary Social Security number, both renewable every two years. Specifically, the program's criteria for applying have been:

- arrival in the United States before the applicant turned 16

- living continuously in the United States since July 15, 2007

- under age 31 on June 15, 2012

- enrolled in a high school or GED program or have earned the equivalent of a high school diploma

- never convicted of any felony or serious misdemeanor

|

| Source: countable.us |

Undocumented Immigrants Express Mixed Responses to the New Executive Action

The new inclusions and continued exclusions from the Deferred Action program are garnering mixed responses from undocumented immigrants and their allies. Those who now benefit from Deferred Action or whose family members are eligible are grateful. Others, such as Armando Ibanez of Los Angeles, worry that their families could be separated since some parents of DACA recipients are still not eligible. Some have already been affected. Yves Gomes, a student at the University of Maryland, has been separated from his parents, who are banned from reentering the country until 2019.

Additionally, some people feel that the tenets of Obama's executive action just don't reach far enough. Since the federal DREAM Act failed to be passed in 2010, DACA and the most recent executive action have been the only nationwide steps toward helping undocumented immigrants. Undocumented college students who qualify for neither DACA nor the DREAM Act, feel "invisible" and "left behind," explains Yvette Yerma, coordinator for Latino/a Student Involvement and Advocacy at the University of Maryland. Even those who benefit from DACA, however, are still disadvantaged compared to their legal peers.

The key to understanding the reach of DACA and its effect on undocumented persons is in the status that it grants. As explained in a study by Roberto Gonzales, Veronica Terriquez, and Stephen Ruszczyk, there is a difference between lawful status and lawful presence, and DACA only grants immigrants the latter. Dr. Irwin Morris, professor and chair of American Politics at the University of Maryland, explains the distinction, which is that lawful status confers access to financial aid, whereas lawful presence merely protects a person from deportation.

Applying for lawful status is difficult due to the bureaucratic process and the dangers and realities that undocumented immigrants face, including financial constraints and past legal records. Yet, the very fact that DACA exists and that the Obama administration plans to put into effect even more measures to help undocumented immigrants' plight shows that tides may be turning in the right direction.

Skeptics Question the Actual Reach of DACA

Although the overall picture for undocumented immigrants is undoubtedly improving, the extent of DACA's impact is still debatable. First of all, its age and residence date criteria were decided completely arbitrarily, excluding a large subsection of the undocumented population. Clearly, more comprehensive legislation to aid undocumented immigrants is needed. But, Dr. Morris suggests, such legislation is probably not forthcoming, despite all the hope generated by the president's executive action.

Secondly, DACA is limited not only in its reach to all undocumented immigrants, but also toward those it deems eligible for lawful status. It is estimated that only 61 percent of those persons eligible for DACA actually applied in its first year. Meanwhile, USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) reports approving over 98 percent of applications, so on the bureaucratic side at least, the program seems to be adequately matching the demand by applicants. Why this disparity? Why don't more qualified young undocumented immigrants apply?

Potential DACA Beneficiaries Still Face Barriers to Achieving Legal Presence

Legal clinics such as CASA de Maryland, as well as other organizations (religious, civic, educational), greatly aid undocumented youth in their accession of DACA. Perhaps, then, mere ignorance of such resources is one of the main obstacles to people applying for DACA. Another reason for the disparity, Dr. Morris explains, is the financial aspect of the application.

Many undocumented immigrants do not have bank accounts, and many have very poor job security due to their unlawful status and lack of a Social Security Number. Also, submitting a DACA application for each family member every two or three years poses a financial hardship for many families. Thus, the cost of applying should be taken into consideration as an area for improvement in future legislation aiming to aid undocumented immigrants.

Ages and Genders of Beneficiaries Point to Various Sociological Factors that Impede DACA Application

Additionally, the fact that one-third of applicants were between 15 and 18 seems to suggest that high schools provide young migrants with access to resources to apply for DACA. Most students enter the workforce after high school, lacking the financial resources to go to college. As such, educational institutions should continue to support undocumented youth, but other pathways should be explored to reach out to young adults who are no longer in school.

Although the overall picture for undocumented immigrants is undoubtedly improving, the extent of DACA's impact is still debatable. First of all, its age and residence date criteria were decided completely arbitrarily, excluding a large subsection of the undocumented population. Clearly, more comprehensive legislation to aid undocumented immigrants is needed. But, Dr. Morris suggests, such legislation is probably not forthcoming, despite all the hope generated by the president's executive action.

Secondly, DACA is limited not only in its reach to all undocumented immigrants, but also toward those it deems eligible for lawful status. It is estimated that only 61 percent of those persons eligible for DACA actually applied in its first year. Meanwhile, USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) reports approving over 98 percent of applications, so on the bureaucratic side at least, the program seems to be adequately matching the demand by applicants. Why this disparity? Why don't more qualified young undocumented immigrants apply?

Potential DACA Beneficiaries Still Face Barriers to Achieving Legal Presence

Legal clinics such as CASA de Maryland, as well as other organizations (religious, civic, educational), greatly aid undocumented youth in their accession of DACA. Perhaps, then, mere ignorance of such resources is one of the main obstacles to people applying for DACA. Another reason for the disparity, Dr. Morris explains, is the financial aspect of the application.

Many undocumented immigrants do not have bank accounts, and many have very poor job security due to their unlawful status and lack of a Social Security Number. Also, submitting a DACA application for each family member every two or three years poses a financial hardship for many families. Thus, the cost of applying should be taken into consideration as an area for improvement in future legislation aiming to aid undocumented immigrants.

Ages and Genders of Beneficiaries Point to Various Sociological Factors that Impede DACA Application

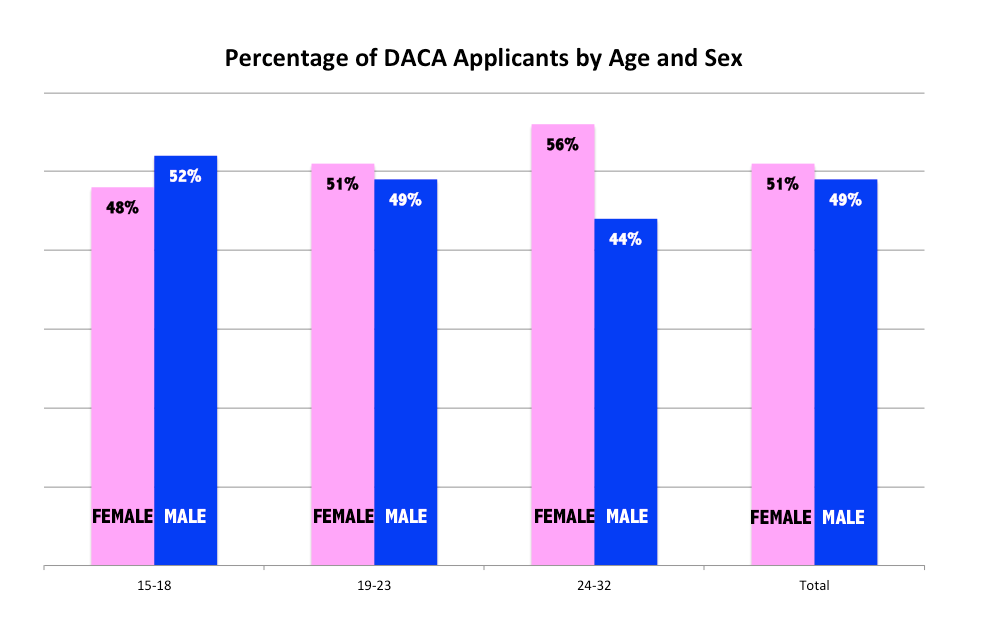

According to Gonzales, Terriquez, and Ruszczyk, "young men in immigrant families tend to experience greater pressures to provide economic or other social resources for their families, while women may be expected to provide direct care and assist with household chores... [and] age correlates with the assumption of adult responsibilities." They hypothesize that these views influence "the types of benefits young adults prioritize."

Compounded with the statistics that male undocumented immigrants tend to drop out of school earlier than their female counterparts, these factors undoubtedly sway the gender ratios of applicants, either because those entering the workforce have more pressing need of a work permit or because those staying in school have more access to legal resources.

|

| Data courtesy of Brookings Metropolitan Policy Program |

If only 48 percent of DACA applicants aged 15 to 18 are female, then the correlation with their lower dropout rates is important to note. Young men who drop out of high school to work may apply for DACA in greater numbers due to their need for a license and work permit, while young women may not see the need.

On the other hand, when only 44 percent of DACA applicants aged 24 to 32 are male, one must wonder why so many more women than men are applying from this age group. A reasonable explanation might be that more men are working full time or that they don't have access to the legal resources or support necessary for applying.

DACA is Necessary Because Living Undocumented is Unpleasant, Unsafe, and Unhealthy

Undocumented status often starts seriously impeding social and economic inclusion of young immigrants when they are old enough to seek employment, pursue higher education, or apply for a driver's license. They are constrained to whatever resources their family, school, and cultural support network can offer them.

Without a Social Security number, many experience a state of constant stress and anxiety, and understandably so. Undocumented persons are at a higher risk of being robbed since they typically carry cash instead of attempting to open a bank account, and if they drive without a license, they worry about being pulled over.

As Janelle Wong, Asian American Studies Program coordinator at the University of Maryland, puts it, undocumented immigrants "just cannot get into any trouble." She cites underage drinking and even as small of a misdemeanor charge as a noise violation as spelling potential deportation for an entire family.

Young immigrants' employment opportunities are also restricted by their undocumented status. Employers will sometimes choose older migrants due to their relatively lower propensity to "refuse tasks or make worker rights claims." The few jobs open to undocumented youth are unlikely to lead to higher employment. Additionally, transportation difficulties can severely limit undocumented persons' work opportunities. Without a Social Security number, they cannot apply for a driver's license. Thus, unless they live in an urban area with excellent public transportation, they must choose between limited job opportunities or the daily fear of being pulled over and discovered.

For these reasons, DACA is crucial to opening doors to professional development for undocumented youth, and to securing their personal safety by enabling them to open a bank account or receive a driver's license--basic actions that citizens and legal aliens take for granted--without fear of potential detention or deportation.

|

| Source: modernsurvivalblog.com |

As Janelle Wong, Asian American Studies Program coordinator at the University of Maryland, puts it, undocumented immigrants "just cannot get into any trouble." She cites underage drinking and even as small of a misdemeanor charge as a noise violation as spelling potential deportation for an entire family.

Young immigrants' employment opportunities are also restricted by their undocumented status. Employers will sometimes choose older migrants due to their relatively lower propensity to "refuse tasks or make worker rights claims." The few jobs open to undocumented youth are unlikely to lead to higher employment. Additionally, transportation difficulties can severely limit undocumented persons' work opportunities. Without a Social Security number, they cannot apply for a driver's license. Thus, unless they live in an urban area with excellent public transportation, they must choose between limited job opportunities or the daily fear of being pulled over and discovered.

For these reasons, DACA is crucial to opening doors to professional development for undocumented youth, and to securing their personal safety by enabling them to open a bank account or receive a driver's license--basic actions that citizens and legal aliens take for granted--without fear of potential detention or deportation.

No comments:

Post a Comment